UPPER MUSTANG, NEPAL - King Angun Tenzing Trandul’s eyes are clouded by cataracts, perhaps from spending much of his 79 years in dim kerosene-smoked rooms. But those eyes, which have witnessed countless changes during his reign, flicker with warmth when his interpreter tells him we are from Canada.

Though obviously exhausted from being placed on display yet again, the king maintains a regal posture on the carpeted Tibetan bench on this late October evening. His faded brocade jacket, wool pants and toque reflect the Chinese and Western influences that have steadily infiltrated his kingdom since it opened to foreigners in 1992.

Above: King Angun Tenzing Trandul.

Upper Mustang, and its capital Lo-Manthang, lie at an altitude of 3,840 metres on the high desert of the Tibetan plateau along the border of Nepal, surrounded on three sides by Tibet. Politically part of Nepal, it’s geographically and culturally Tibetan. Travel to the area is restricted and costly.

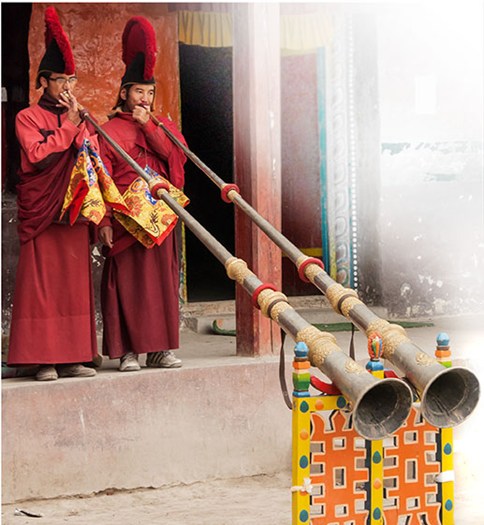

Through the palace walls we hear the din of cymbals, whining trumpets and the rhythmic pounding of drums. Buddhist monks are busy preparing for Duk Chu, the next day’s festival of dances and prayers marking the coming of winter.

A single solar light scarcely illuminates the majestic red pillars supporting the roof of this former grand residence. The five-storey white-washed, mud-brick structure was built around 1400 and stands proudly inside the walls of the once-isolated city founded in 1380 by the king’s ancestor, Ame Pal.

My husband and I have trekked for six days alongside and often across the ankle-jarring pebbles of the Kali Gandaki riverbed from Jomson.

Six mornings of blasting winds, sand grains biting at our skin, swathed bandit-like in buff neck tubes, hats, sunglasses and long-sleeved shirts. Six nights of camping in dusty packed-earth courtyards, our tents protected from fierce afternoon sandstorms by rudely constructed mud-brick walls.

By day, we communicate with hand signals, our words snatched by noisy gusts. By night, we discover sand in our ears, caked on the sweaty interior of our sunglasses and deep in our wool hiking socks.

And every step has been worth it.

We’re here to reconnect with the Tibetan culture that seized our souls during a recent visit to Lhasa. We want to witness what is left of an ancient civilization, no longer forbidden to the outside world, and investigate any changes caused by 20 years of tourism.

Wangyal Gurung, our local guide, tells us that the king walks through the city every day.

Awakened at 6 a.m. the next morning by the wail of trumpets heralding the final Duk Chu rehearsal, I follow the king’s usual route, slipping through the single city gate to mimic his customary dawn excursion.

The king, reduced by the Nepalese government to the rank of Raja in 2008, has witnessed myriad changes in his lifetime, the most dramatic during the past two decades when foreigners have been allowed access to his kingdom.

French explorer Michel Peissel, whose pioneering visits opened this region to Western awareness in the 1960s, described the town then as “one great cement block, laid down upon an inferno of barrenness by the hand of some warring god, with houses packed like cubes within the walls.”

Now shops, guesthouses and campgrounds sprawl outside those once-impregnable barricades.

Along the outer perimeter of the walled city a parade of several hundred gritty gray goats snakes along narrow streets toward meager mountain pastures. The 12-year-old herder nods and carries on.

Women gossip at the communal water source, trekkers sip steaming tea by their tents inside stone-walled camping compounds and expedition cooks line up at the kerosene depot vying for rare fresh fruit and vegetables demanded by clients.

Scruffy dogs scramble for spots of sun in front of countless houses now spilling outside the walled fortress.

The shell of a partly constructed three-storey stone guesthouse dominates one end of the street.

The air is fragrant with yak and horse dung.

Above: Trumpeters signal the kid's arrival and subjects come and pay their respect to the monarch.

Inside the expansive monastery square, lined with red-pillared balconies, we meet Tsering Tashi, the genial monk who is principal of the Choedhe Monastery School. As former teachers, my husband and I are interested in the education of local children.

“How has the influx of tourists changed life for you and your students?” I ask.

He smiles warmly. It seems he’s glad to be asked. He is well-travelled, well-spoken and has strong opinions on the subject.

“Sometimes we feel like animals in a zoo,” he says. “And the $50 a day foreigners pay to come to the restricted area? We don’t see any of it. We’re supported mainly by foreign foundations.”

Later, in search of local artefacts, we visit the Lo-Manthang Souvenir Shop owned by Pema Bista, the entrepreneurial owner of the guesthouse under construction outside the walls.

A Tibetan from Shigatse, 300 kilometres west of Lhasa, he married a Lhoba woman and has made Lo-Manthang his home for the past 20 years. His wares are almost exclusively Tibetan: prayer wheels, statues of deities, prayer beads and hand-crafted jewellery bought at the Nepal-Tibetan border during the annual August market.

After a lengthy bout of bartering for a delicately carved jade and silver bowl, we settle on a price. Trust built, we sit down on a narrow Tibetan bench to talk.

“So what do you think of all the foreigners coming to your home?” I ask.

“The changes tourism has brought are all good,” he says. “Small businesses are starting, like camping and supplies. More outsiders are coming to sponsor schools and a hospital. My children are learning Tibetan, Nepali and English.”

We wander down a few doors and duck through the low-curtained entrance of a tiny shop. Third generation shopkeeper Karma Wangyal, a native of Lo-Manthang, isn’t so positive. A slight man with long black hair curling over the collar of his leather jacket, he seems pleased to be asked for his ideas.

“How do you feel about the restoration of the monasteries?” I ask.

“I have respect for the American Himalayan Foundation and Italian artist Luigi Fieni, who worked with locals to restore monastery structures and artwork,” he says.

“They revitalized our Buddhist culture, but also showed others the value of ancient treasures. Last winter, priceless artefacts were stolen from a stupa outside the city, between Tsarang and Lo-Manthang. It’s not all good.”

“What about trekkers who support souvenir shops, food stores and camping areas? And tourists who want to buy traditional Lo-Manthang crafts?” I ask.

“Most souvenirs are from Tibet and do not represent our culture. There aren’t many local artists left. The skills have been lost,” he says. “I worry about my children losing their identity. Western dress and English dominate the tourist trade.”

Though chilled by fierce afternoon winds and growing cloud cover back out in the square, we’re enchanted not only by the demon-chasing ceremony but also the ruddy, wind-calloused faces of the locals gathered for the occasion.

Twenty years of outside influence are evident. Married women still wear traditional chupa dresses with striped aprons. Monks are resplendent in maroon and saffron robes.

But Wangdyal Gurung, our local guide, is dressed for the occasion in a Chinese lamb fleece-lined brocade jacket, over blue jeans. And most children sport Western-influenced jackets, ball caps and tracksuits.

When the three-hour ceremony winds down, we reluctantly return to our tents to prepare for the dusty six-day return trek. We snuggle into sleeping bags and dream of the countless prayer-flag bedecked mountain passes ahead. Too soon we will catch the plane from Jomson to Kathmandu, leaving the ancient city.

We’re glad that, like Shangri-La, it will remain protected from outside influence, at least until spring.

Information

The reign of Jogme Dorje Palbar Bista officially ended on Oct. 7, 2008, by order of the Nepal government. The former king maintains the title of Raja and the respect and loyalty of his subjects. / The Nepalese Department of Immigration requires foreign visitors to obtain a special permit - $50 per day, per person - and employ a guide to protect local tradition from outside influence as well as to protect the environment. / The Nepal Planning Commission and the National Trust for Nature Conservation have collaborated with the United Nations Environment Program to develop a Sustainable Development Plan for the Mustang District for 2008 – 2013. / Accommodation: Camping or extremely rustic guesthouse. / Cost: $3,200. Trips start & end in Kathmandu. / Climate: Dry, strong winds, usually beginning late morning, and intense sunlight; Temperature: 26C to -20C; Rainfall: Less than 200 mm annually / Getting there: From Kathmandu, drive to Pokhara, then fly to Jomson. From Jomson it is a six day trek or five days by horseback to Lo-Manthang. Helicopter from Jomson to Lo-Manthang is an option but the scenery and culture on the trek is not to be missed. Sections of the new road can be managed by four-wheel drive vehicles but road conditions vary greatly, particularly during monsoon season.