YASUNÌ NATIONAL PARK, ECUADOR - The Ecuadorian leafcutter ants are bustling along the highway at our feet, like Friday evening rush-hour traffic on a one-lane highway home. Bumper-to-bumper, head-to-toe, and every one has a parcel — a blade of grass, a section of leaf, a piece of something — which they are taking to their destination. They all have a purpose, and are steadfast in their approach to get their task accomplished.

With the bright sun overhead, and the Añangucocha Lake stretched out in front of us, Jiovanny Rivadeneira and I sit on the grassy knoll between villas at the Napo Wildlife Centre (NWC) and talk about the local community and how it spawned the successful NWC. Throughout our chat, I keep looking at those industrious and relentless ants and think how much Rivadeneira’s story is so similar, in tenacity, work ethic and personal sacrifice.

For a long time, the community here was stagnating. Birth rates were down, and the young, once old enough, were leaving for bigger centres. There was nothing to hold them back, no future to look forward to. The population was dwindling and the future of the community was in peril.

Rivadeneira, a community elder and leader and the general manager of the NWC, is one of 13 children. He was always a dreamer growing up, the thoughtful one. He was a visionary of sorts, and as he grew older and became wiser, he recognized that there had to be change or the consequences for his beloved community would be catastrophic.

When the time was right, Rivadeneira became the leader of the community council and started his quest of revitalization. But this was not a dictatorship, so his vision had to be sold to the council and voted upon. At the time, the council was leaning heavily towards getting involved with the oil companies that wanted to buy lands to get to the vast oil reserves locked beneath. This was easy money and a quick fix, a get-rich-quick type of deal. Big money.

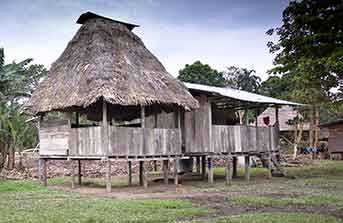

Left: One man is fighting to save some of the rarest animals on earth. Right: By saving the rain forest, Ecuador is saving a culture.

However, Rivadeneira saw the consequences of that option, how the encroachment of the oil companies, once started, would eventually change the landscape of the rainforest forever. He opted instead to campaign with his peers on the council to build an Eco Reserve to earn money to keep the community alive, provide employment for the young and build and renovate the community infrastructure.

He had the foresight to think that foreigners would pay money to see the rainforest from within, to stay in the warm belly of the Ecuadorian Amazon, to marvel at nature at its best, to see and experience the traditions of the local peoples — to live, for just a while, inside the Yasunì National Park, an important UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and the largest tract of tropical rainforest in Ecuador. Years later, history has proven him right.

But this was not without personal sacrifice.

“Many nights I cried,” recalls Rivadeneira. “I had to make so many personal sacrifices, family sacrifices, for the greater good of the community, while non-supporters had great lives with their families.”

Today, however, he smiles. Broadly. Things are coming together. The NWC is working on a scientific study with a local university. The Interpretation Centre — situated in an authentic Añangu village building with a woven grass roof and dirt floor — is where the community women’s association sells handmade traditional handicrafts, where you can see demonstrations of traditional ways of hunting and fishing, and enjoy performances of traditional dances. And you can try your hand at shooting blow darts through a two-metre-long blowgun; not nearly as easy as it looks!

As honoured guests, we are treated to an exclusive tour of the community itself, a social outing usually off limits to visitors.

In the village we see the new Vicente Mamallacta School, boasting around 92 students. The school offers specialized courses in ecotourism, language and agronomy, subjects that best fit the practicality of the community. The top graduating students have the option of getting a job or a scholarship, paid for by the community.

But we have come to see wildlife and to experience the rainforest from within. And we are not disappointed. During our three-day stay, we see plentiful displays of wildlife: caimans, sloths, turtles, lizards, squirrel monkeys and scores of birds, including kingfishers, hawks and the screaming piha, probably the loudest bird ever, and, of course, the hoatzin, also known as the stinky turkey or stinkbird. A rather noisy but always entertaining species with a variety of hoarse calls, including groans, croaks, hisses and grunts.

And insects? This is insect central. Iridescent blue morpho butterflies the size of dinner plates live here. Caterpillars six inches long with long fuzzy sweaters lounge on giant leaves, eating their furniture one bite at a time. Moths, giant grasshoppers, huge beetles … just too many to list.

We are gently woken by a polite knock on the door — there are no alarms here — at 4:30 every morning, get a bite of breakfast and then we go hiking, sometimes for hours. One day we hike to the best parrot clay licks in Ecuador to see the beautiful birds get their daily mineral fix. From the blind we see no fewer than five species, including the mealy amazon, blue-headed and orange-cheeked. Then we’re off to another clay lick that parakeets frequent. Hundreds of them buzzing around, watching for predators, always alert and skittish. Land to get their mineral fix. Take off. Hide. Come out again. Repeat.

Amazing.

Another day, we hike for an hour to get to the canopy observation tower — so aptly named — and once we make the 36-metre climb we were mesmerized by the antics of a family of howler monkeys grooming each other atop a tree. Moments later, a group of macaws fly by in the distance, effortless, barely above the morning mist and glowing warmly in the rising sun. We spot a lettered araçari, a cousin of the toucan, and we’re delighted to have a visit by a kite, a bird from the hawk family. Tarantulas larger than my hand make the tower their home, as well.

In the evening, paddling along a tributary by canoe after dusk, I feel closer to the rainforest than in the daylight. It envelops me in a calming black curtain – not silent, but still. Nighttime sounds come from everywhere. A shriek here, a howl there … clicks, whirs and cackles. In the light of the moon I can make out the twisted mesh of vegetation spilling over from the canopy above reaching into the water next to our canoe.

Later, we catch the red reflections from inside a caiman’s eyes by powerful torchlight, both up close and across the kilometre-wide lake.

Like the caiman that night, we too were red-eyed when we finally had to depart.

About the Author

From tracking and naming a female Humpback Whale in Moorea, near Tahiti; in a hot air balloon adventure over the Napa wine valley, to visiting a native community two hours by canoe into the depths of the Ecuadorian Amazon, Mark has brought many adventure travel stories and images to readers across the country. A freelance contributor to TraveLife magazine, Mark also is a regular contributor of travel features to ExtraOrdinary Health Canada Magazine; and has been published in the Toronto Star, the National Post, and Air Canada’s EnRoute magazine, and in Photographer’s Forum: Best of Photography. Mark studied photography at Toronto’s Ryerson University. Mark’s been fortunate enough to travel to places many people dream of in addition to those mentioned previously; The Galapagos islands, Bora Bora, Taha’a, Raiatea, Costa Rica, extensively through the Caribbean, Puerto Rico, Mexico, Florida, California, Alberta, B.C., England and Scotland. Favorite spot? That’s a hard one – there have been so many but at the end of the day it’s no contest: Bucket list Bora Bora.